-

The political implications of territorial inequality in Caracas, Venezuela

2020

Texto published in Limes - Rivista Italiana di Geopolitica

Inequality is commonly associated with the distribution of income and economic opportunities, but it is also evident in the built environment. This is especially true in the countries of the "global south," such as Venezuela, where informal settlements make inequality blatantly visible. This article will attempt to unpack the drivers that led to the formation of a “city within a city”, the political division of Caracas, its relation to the barrios and the territorial divide it generated, as well as an analysis of critical places and infrastructure significant to gaining or maintaining control of the city in the face of rising levels of unrest and conflict.

A CITY WITHIN A CITY

During the mid-20th century Venezuela’s income drastically increased with oil production and the dictatorship, led by Marcos Perez Jimenez, was eager to quickly reshape the country into a bastion of modernity and progress. Caracas, the country´s capital since colonial times,1 went through an ambitious agenda of construction that sought to express this nation-building effort through modern architecture and infrastructure. The Humboldt Tower and the cable car essentially conquered the Avila mountain. Built in 1956, it was designed as a luxury hotel with a covered swimming pool, casino, bar, restaurant and ballroom.2 Other examples include the Central University, a 400-acre modern campus built in 1953 and now Unesco World Heritage Site. The Simón Bolívar Center came a year later and graced the city with its own 103 meters tall twin towers that were the tallest buildings in Venezuela at the time. The Helicoide reshaped a mountain into an ascending helix to serve as a linear shopping mall. Just shy of finishing, construction came to a halt in 1958 with the fall of the dictator. Today, it is the headquarters of the SEBIN (the equivalent of Venezuela’s CIA) where many of the most prominent political prisoners are held. And lastly, a 4-lane freeway, financed by the Rockefellers, sanctified Caracas as a car city and occupied the entire axial center of the valley.

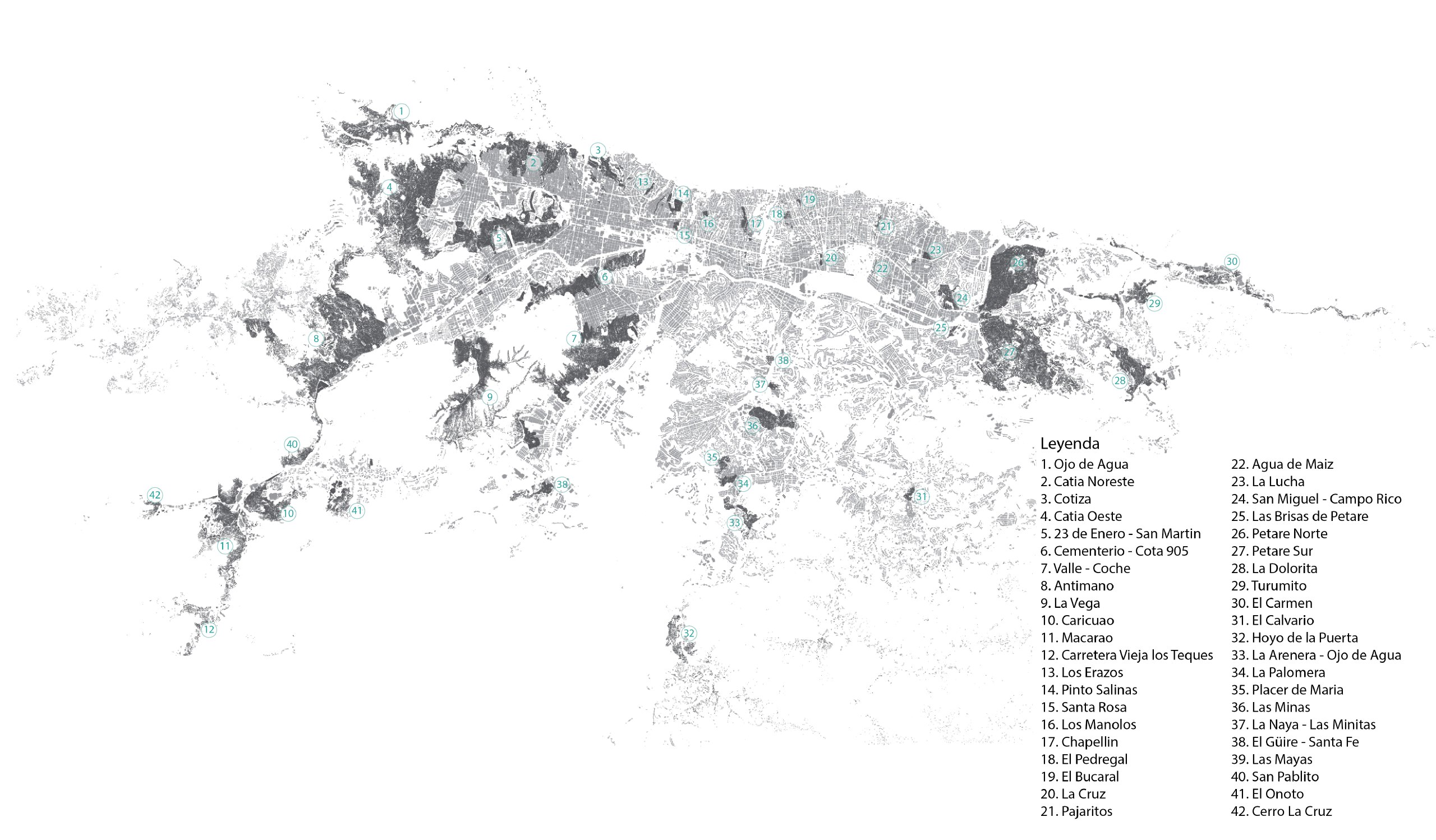

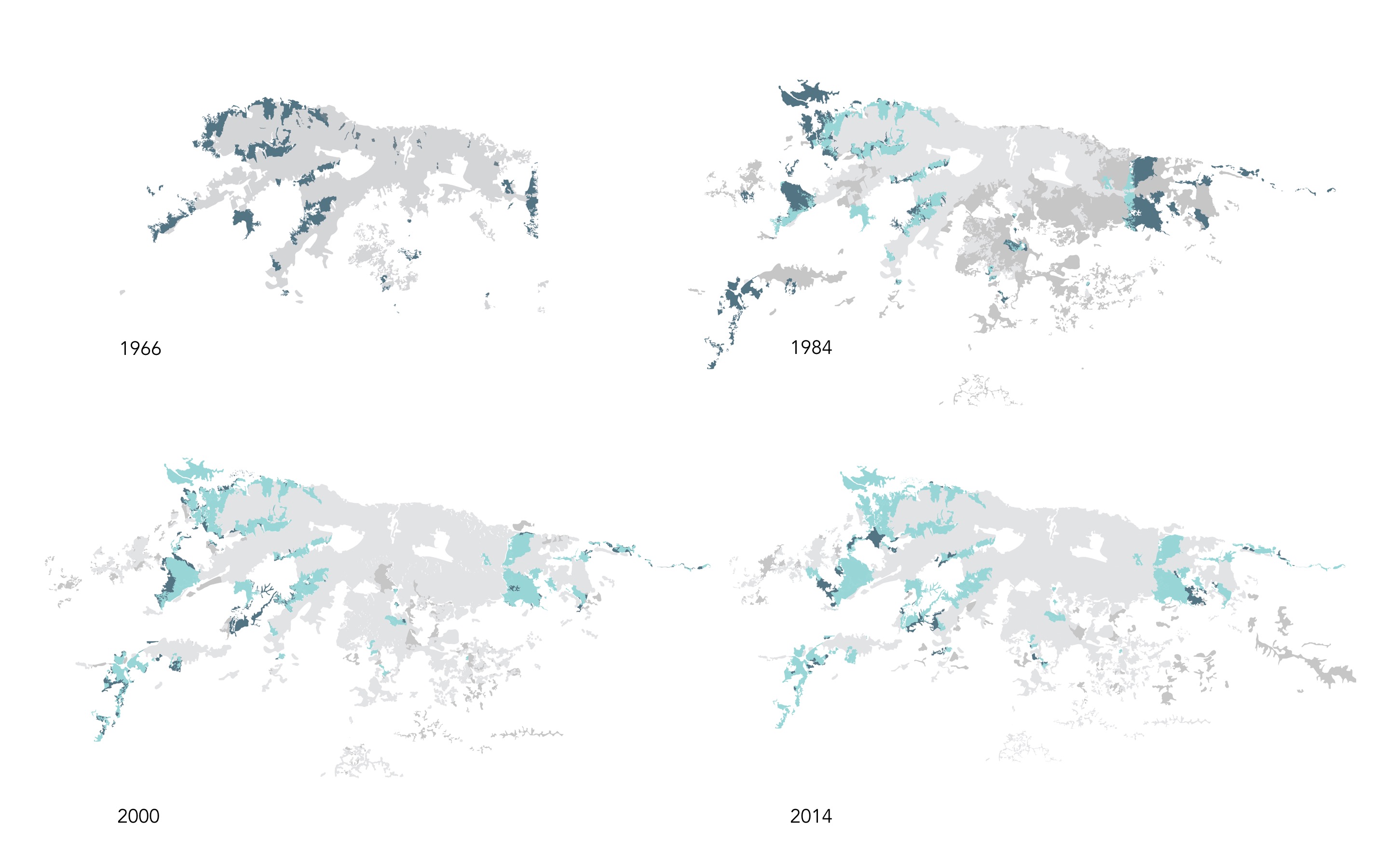

These are widely praised exemplars of modernity and progress that were enviable to the eyes of the world at the time. However, there is also another story, one far less acknowledged, that transpired in parallel all along these years. Informal settlements in Caracas grew at a much faster rate than the rest of the city. Already in 1966, they covered 17% of the urban territory; in 1983 36% of the population lived in them, today the percentage has increased to 45%. (Fig 1) Oil production which began in the 20s and significantly increased in the 50s, created a large industrial and service sector to support the oil economy that motivated migration toward cities. At the same time, agricultural production, mainly in the form of coffee plantation, was in decline as markets in Brazil and Colombia had become more competitive and were arguably producing better quality beans. Therefore, even though oil production is often blamed for the ruin of agriculture in the country this is not entirely true.

In Caracas, the informal settlements, or barrios as they are called in Venezuela, were the direct result of migration. They grew on the hills that surround the city, in plain sight, at a rate 2.5 times faster than their "formal" counterpart.3 (Fig 2) However, both the government and the private sector preferred to deny it or continue believing that the economic bonanza of oil would effortlessly resolve it, ignoring the growth of a deep social discontent that was the perfect brew for ensuing populist movements that would later emerge.

In 1988 the Caracaso, ignited a massive popular protest, mainly among people living in barrios, against higher gasoline prices and higher public transportation costs. A military takeover of the streets led by the then president Carlos Andrés Perez, to quell related looting resulted in hundreds of deaths and thousands injured. Hugo Chavez, whose first attempted to enter into power by force occurred in 1992 and then succeeded through elections in 1999, cultivated and institutionalized this discontent and the rest is now history.

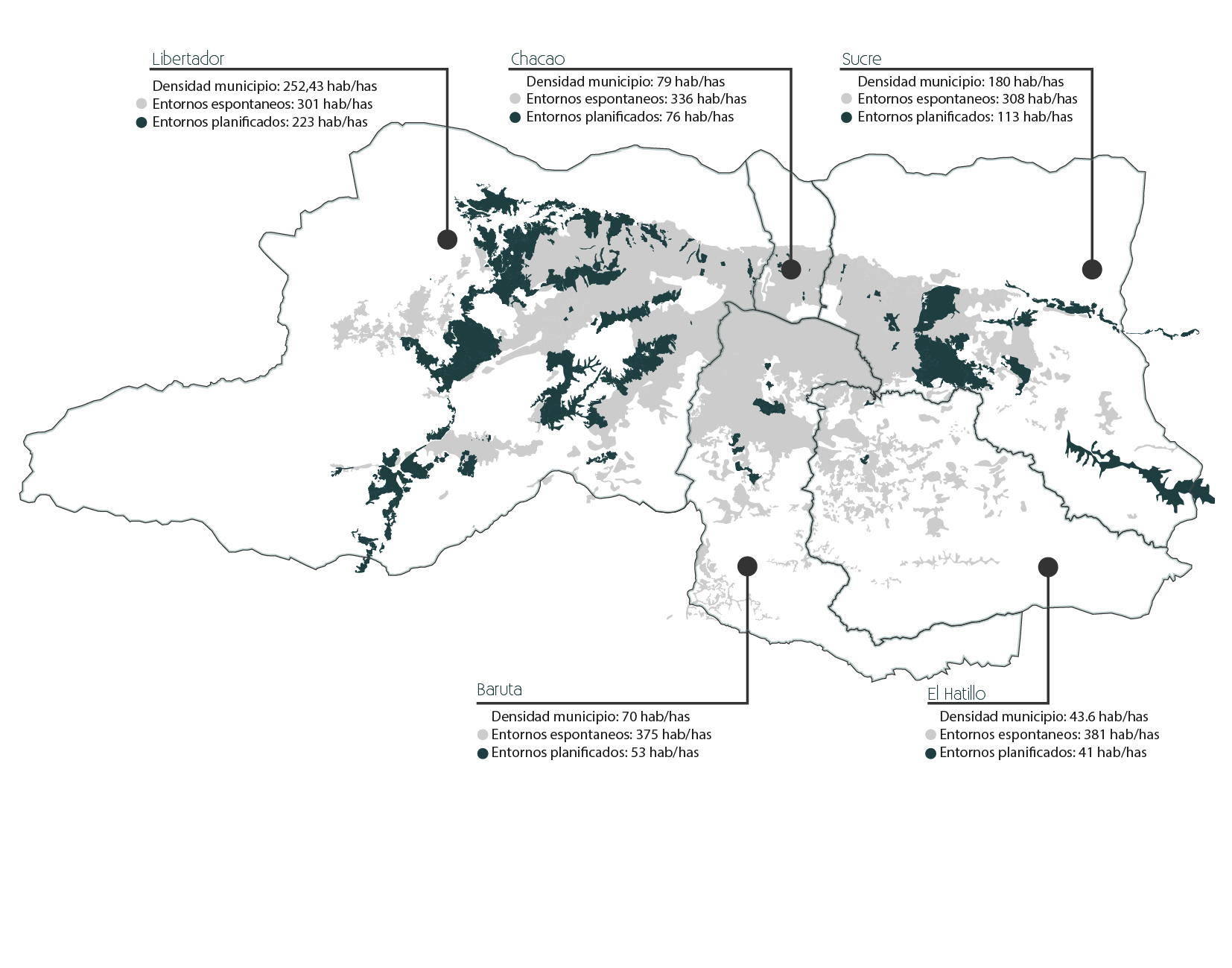

DECENTRALIZATION

The city of Caracas itself was subdivided into 3 then 5 municipalities, in 1989 and 1992 respectively, as a result of the decentralization laws that were passed during the administration of Carlos Andrés Perez. (Fig 3) The intention of these laws was to strengthen local government and create structures that could better serve the needs of citizens not only in Caracas but throughout the country.4 These municipalities had mayors that were elected through public elections and most often represented either of the two dominant political parties at the time, the Cristian Party Copei, and Acción Democratica AD. In 1992 El Hatillo was created as a new municipality and Chacao was fractioned off from what was previously a larger Sucre municipality. These territorial divisions represented an opportunity for municipalities to concentrate wealth. In the case of Chacao, it is the site of many bank headquarters, as well as other financial institutions, brokerage houses, investment funds, and transnational companies. By having their address in Chacao, an important source of revenue for the municipality came through property taxes. In the case of El Hatillo and Baruta, these are areas of the city that where undergoing important urban development during the late 80s and 90s and even into the first decade of the 21st century, with large new shopping malls and residential neighborhoods. The municipality´s interest was to support developers who were creating new housing for the middle- and upper-class segments of the population, which in turn would generate taxable income. 10 years later, with the appearance of Chavez in the political scene, the five municipalities of Caracas become an important political scenario for power. The result of the 2000 elections was that Libertador, which is the largest of the 5 municipalities and has a population of 2.2 million, and the only one in the Federal District, was won by a chavista mayor and has continuously been government by a chavista ever since. Three municipalities, Chacao, El Hatillo and Baruta have always elected opposition mayors. Sucre, was initially governed by a chavista mayor, but then in 2008, an opposition candidate won the elections and it became an opposition municipality for the following 9 years.5 More people live in the Libertador municipality than the other 4 municipalities combined, in fact over two thirds of caraqueños live there. Informal settlements are much more prevalent in Libertador than any of the other municipalities, and represent nearly 1 million inhabitants. Sucre municipality has close to 400.000 inhabitants living in informal settlements, and Baruta, Chacao and El Hatillo combined only have 80.000 barrio dwellers.6 (Fig 4) You would expect voting patterns of each of these municipalities to correlate with its urban morphology. People living in informal settlements tend to have lower incomes, feel disenfranchised and are more likely to support the chavista regime. It is not surprising that Sucre and Liberator are the municipalities that have had chavista mayors. In the case of the Libertador municipality, 45% of its inhabitants live in informal settlement, in 37% of its urban territory.7 In the case of Sucre municipality, more than half of the population, 58%, lives in an informal settlement, however the area they occupy is only 35% of the municipality´s urban territory. When we go into the other 3 municipalities, Baruta still has a significant population that lives in informal settlement, 28%, but they are concentrated in 5% of the urban footprint.8 In El Hatillo, people in informal settlements represent 7% of the population and live in less than 1% of the area. And, in Chacao the population living in informal settlements is 2% and they occupy 1.2% of the territory.9 The higher concentration of people living in informal settlements translates into higher population densities. The average population density in the barrios is 300 inhabitants per hectare (p/has), whereas the formally disposed parts of the city are 41 p/has in El Hatillo, 113 p/has in Sucre and 223 p/has in Libertador.10 (Fig 5) These density variations reflect very different living environment, that are closely tied to levels of inequality.

THE POLITICAL WALL OF CARACAS

Barrio dwellers, especially those living in Petare which is said to be Venezuela´s largest barrio, (see Fig 4) located in Sucre Municipality, began relinquishing their unconditional support for Chavez as the years progressed. In fact, barrio dwellers elected the opposition mayor, Carlos Ocariz in 2008 revealing that the tendency to associate people living in informal settlements with chavismo was no longer entirely accurate. As this happened, a divide began to appear more starkly in the urban fabric. Once Sucre became an opposition municipality, the line along the Chacaito Creek dividing chavistas from the opposition, became very pronounced. The Chacaito creek is much more than a stream of water that runs from the Avila Mountain to the Guaire River in Caracas. It represents a political division in the territory that separates the Federal District to the West from the State of Miranda to the East. It is also the line the divides Libertador and Chacao. Curiously, the Sabana Grande Boulevard which connected Caracas in the east with to the colonial town Petare (today part of Sucre municipality) and Los Chorros where people would spend their summers in the late 19th century, straddles both municipalities. Throughout most of the 20th century it was an important commercial thoroughfare, and was made into a partially pedestrian boulevard when the metro system was installed in the 1980s. More recently it was the subject of an urban renewal project, sponsored by the central government through Pdvsa, Venezuela´s oil company, that was initiated in 2007 to create a more amenable public space along this 1.6 km urban corridor.11 The interesting thing about the project is that even though its geographical length includes part of Chacao, extending all the way to the Chacaito Plaza, funding and the project scope ended precisely at the line of the creek. In other words, no investment would be made on the other side of this line, since it implied benefiting people from the opposition. It became clear to Chavez that the municipal structure of the city was not beneficial to him, and so he began to devise a plan to do away with it altogether. During his time, decentralization efforts were reversed and municipalities were stripped of their jurisdictions over health and education, which were returned to the central government. Chavez thought to create a different territorial organization based on “communes.” The first implementation step of this new structure took shape through the Consejos Comunales, which are neighborhood organizations that represent approximately 400 families, registered directly with the central government. Most of the consejos comunales were formed in barrios, because they were interested in taking advantage of the opportunity the government offered through this new structure to formulate projects for their community and present them for funding. People had the sense they could access Chavez directly, which proved to be a very powerful political devise. To date I have not known any examples that successfully received funds for a proposed project. The whole initiative seems to have been more about increasing control over communities, than facilitating the transference of resources. The comunas in turn, would comprise several consejos comunales. The consequence of this new social order was to further atomize and fragment the community structure within the barrios. For example, a barrio might have had several sectors within it that reflected the way it grew over time. La Morán, in the western side of Caracas, was initially comprised of 5 sectors. When the population was asked to form consejos comunales, this structure was further fragmented, so that in La Morán now you might find 12 consejos comunales. Because they are financial units that are exclusive, meaning, if you are within one, you are not part of the next one, this has created very strong barriers within the community. Essentially a feudal structure has emerged, complete with animosities developed in this relatively short amount of time, making it very hard for them to negotiate, agree and much less work together.

A VULNERABLE CITY

Caracas is in a long and skinny valley that runs east-west. It only has 4 access points, one from the east through the Guarenas-Guatire highway, one from the northwest through the Caracas-La Guaira highway, one from the west via El Junquito, and one from the south with the Valle-Coche highway. Blocking these four ground entrances would quickly and completely isolate the city from outside communication. (Fig 7 map of critical points in Caracas) Other strategic sites are the Miraflores Palace, which is the presidential office and residence, the Central Bank, the Defense Ministry, telecommunication stations such as Telesur and VTV and the basins that provide water to the city. The Sebin´s headquarters known as La Tumba and El Helicoide, where prominent political prisoners are held are particularly sensitive sites for the evidence they protect regarding human rights violations. The government´s key military bases are La Carlota Air Base and landing strip and Fuerte Tiuna. La Carlota represents another important way to enter the city, that however, can only be accessed by the official government. Fuerte Tiuna concentrates important military operations, but its land use has been altered in recent years with the introduction of multifamily social housing structures. This new hybrid condition is thought to be intentional in order to increase collateral damage through human shields should confrontations ensue against international forces. It is problematic to speak of an “armed” conflict unless it were to involve outside international entities. Within Venezuela, the only armed groups are the military themselves, police forces and civil pro-government groups called “colectivos.” The great majority of the population, however, is completely unarmed. The colectivo’s stronghold is in the 23 de Enero neighborhood (a massive multifamily social housing complex built in the 50´s during the Perez Jimenez dictatorship) and its surrounding barrios (see Fig 4) just west of the Miraflores Palace. It is a place that gives every indication of being pro Chavez and pro Maduro through elaborate mural paintings and signs, as well as carefully maintained public spaces, ball fields and scattered chapels with shrines to Chavez throughout the residential complex. It was ironically the site that decided the end of the Perez Jimenez dictatorship 60 years ago when confrontations between civilians and military tanks convinced generals to relinquish their support for the dictator. Up until recently you could still find bullet hole marks on the facades of buildings.12 Other areas that are very sensitive and important to the government are not in Caracas. Much of the wealth they still have access to is in the country’s southern territories. The Arco Minero, where gold is being extracted on a regular basis, albeit with highly irregular techniques, is key to the government´s finances. The sites where petroleum is still being extracted and the paths that link the oil to exportation routs are also key sources of revenue. These are sites that are in the government´s interest to control, probably even more so than the capital itself.

THE END OF CHAVISMO HEGEMONY

The tendency of waning support for chavismo accelerated with Maduro´s presidency which started in 2013. The reasons are fairly obvious: rampant inflation, waning quality of life, decreased quality of public services and most importantly food scarcity. The scant support the government enjoys today is artificially maintained through assistance, delivered through “missions” such as the CLAP (Comité Local de Abastecimiento y Producción) boxes, which are only given to people who consistently prove their affinity for the political party.13 Securing basic sustenance is so challenging in Venezuela now that the mere possibility of having access to a modestly priced box of food is enough for people to remain aligned with Maduro; they don´t know an alternative. But still the general population is very disappointed with the way their lives have evolved and lament their much-diminished quality of life. People in general do not ingest enough calories for themselves and their families; on average people have lost 10 kgs. of weight over the past two years.14 Allegiance to Maduro is precarious and based on the fear of losing the few privileges being pro-government affords. People in the barrios, have also felt the oppression of the regime through very arbitrary assassinations of young men believed to have murdered police officers. The OLPs Operación para la Liberación del Pueblo, have created deep resentment among barrio inhabitants toward the government.15 The assassinations occur without due process, without even having clear proof of the victim´s identity before killing them. The most infamous cases have taken place in the barrios Cota 905 and El Valle. (see Fig 4) Within Caracas support for Maduro or Guaidó does not correlate any more with the ideological divisions that were present for the last two decades between the official government and the opposition. Most citizens today are simply fed up with the low quality of life, high levels of crime, food scarcity, terrible access to health and medications, inefficient public services and a collapsed economy. Those who appear to be enthusiastic Maduro supporters are either very scared to lose the few social benefits they still receive, or have vested interests in the government because of close ties to military generals. This conditioned enthusiasm, however, only reflects a small portion of the population. People might still remember Chavez with affection, but you are hard pressed to find the same endearment for Maduro. Not surprisingly, within this vacuum of enthusiasm and collective hardship, 81% of Venezuelans want Maduro to step down.16 Change though, does not depend on not how popular Juan Guaidó, the National Assembly´s President turned Interim President, may be. Change is entirely dependent on whether the military, which grew from 70 to 200 generals in the span of 10 years, will relinquish its support for the official government. The choice on their part is not easy since they enjoy extensive access to preferential dollars,17 importation businesses, affiliations with drug distribution, and other very lucrative illegal sources of income that have kept them loyal to Maduro. Furthermore, the government learned from Cuba the importance of eliminating any possible sources of rebellion or divergence within the military early on. The generals that remain in their positions today are tightly coalesced behind Maduro, because it is in their interest to maintain their lifestyle and access to wealth. However, important advances within the international scene have helped limit the movement of money and resources. The hope is that somehow this will change the game enough for key generals to decide that they will no longer back Maduro. Meanwhile the 30 million people that still live in Venezuela suffer the consequences of the military´s greed and selfishness on a daily basis. Many are even losing their lives for absurd and unforeseeable reasons: blackouts that affect people whose life depends on respirators, dialysis etc; diseases obtained by ingesting contaminated water; lack of access to medical attention or medicines, famine and malnourishment; in the case of political prisoners, torture and abuse; homicides by police and military forces; not to mentions petty crime and gang violence. Children and university students are no longer going to school; people cannot move because there is hardly any public transportation left to speak of; stores, shops and commercial entities cannot operate if they cannot charge people electronically, and printed money stopped working long ago due to inordinately high levels of inflation; offices cannot work without computers and internet; and for everyone at home, cooking, bathing and cleaning are enormous challenges because of limited access to water, not to mention the frustration of watching unrefrigerated food spoil. The country has really come to a standstill. While the current situation undoubtedly stems from previous years of neglect, what is happening now is unprecedented and an exaggeratedly steep price to pay. As inequality manifested itself on the hills of Venezuela in the 50s, the government and private sectors responded with denial and evasion. As wisely stated by a rather controversial author, “you can ignore reality but you cannot ignore the consequences of ignoring reality.”18 We should feel some relief in the fact that at least this time, reality can no longer be ignored.

Notes

- Caracas has been the capital of Venezuela since 1577, only 10 years after it was founded by Diego de Losada in 1567 as Santiago de León de Caracas

- The Humboldt Tower was built in 1956 under the regime of Pérez Jiménez and designed by architect José Tomás Sanabria.

- Esta tasa de crecimiento la afirman los estudios de Federico Villanueva y Josefina Baldó en el Plan de Habilitación Física de Barrios de 1996.

- Ideana Berosca Rincón Soto. “El proceso de la descentralización en Venezuela en el marco de la nueva Constitución Bolivariana.” Gestiopolis, December 07, 2009.

- In 2017, the municipality went back to being run by chavista mayor José Vicente Rangel. However, this election is broadly understood to have been fraudulent.

- Elisa Silva et all. CABA: Cartografía de los barrios de Caracas 1966-2014. (Caracas, Fundación Espacio, 2015)

- Ibid

- Ibid

- Ibid

- Ibid

- The renovation project included the design of the pavement and drainage, which was done by Enlace Arquitectura as the result of winning a design competition in 2007. The project was built between 2009 and 2011 and won the VIII Iberoamerican Architecture and Urbanism Biennial in 2012.

- Alejandro Velasco Barrio Rising: urban popular politics and the making of modern Venezuela. Oakland: University of California Press. 2015

- Another “mission” that proved very successful to buy the loyalty of people was the project Gran Misión Vivienda Venezuela GMVV, which built 8,000 homes in Caracas, mostly in the Libertador municipality.[13] People felt that if they kept their allegiance to the party in the end, they too would benefit from the opportunity of having a free house.

- Victor Samerón. “Susana Raffalli: ‘La idea de que esta crisis la vamos a resolver con ayuda humanitaria es un mito.’” Prodavinci. https://prodavinci.com/especiales/el-hambre-y-los-dias/entrevista-raffalli.html (accessed March 23, 2019)

- Daniel Marco, “Una pena de muerte disimulada”: la polémica Operación de Liberación del Pueblo, la mano dura del gobierno de Venezuela contra el crimen,” BBC, November 28, 2016. https://www.bbc.com/mundo/noticias-america-latina-38126651 (accessed March 23, 2019)

- __”81% de los venezolanos quiere que Maduro deje el poder, según una encuesta” Perfil, January 8, 2019. https://www.perfil.com/noticias/internacional/el-81-de-los-venezolanos-quiere-que-maduro-deje-el-poder-segun-una-encuesta.phtml (accessed March 23, 2019)

- Preferential dollars refer to dollars that can be obtained at the “official” exchange rate against the bolivar, Venezuela´s currency, which is fixed by the government.

- Ayn Rand at lecture delivered at the University of Wisconsin in 1963