-

Real-ize the integrations of cities through drawing

SURLab

2022

This article was commissioned for SURLab´s publication "CoProduction of Public Space: Persepectives and Experiences from Latin American Informal Neighborhoods"

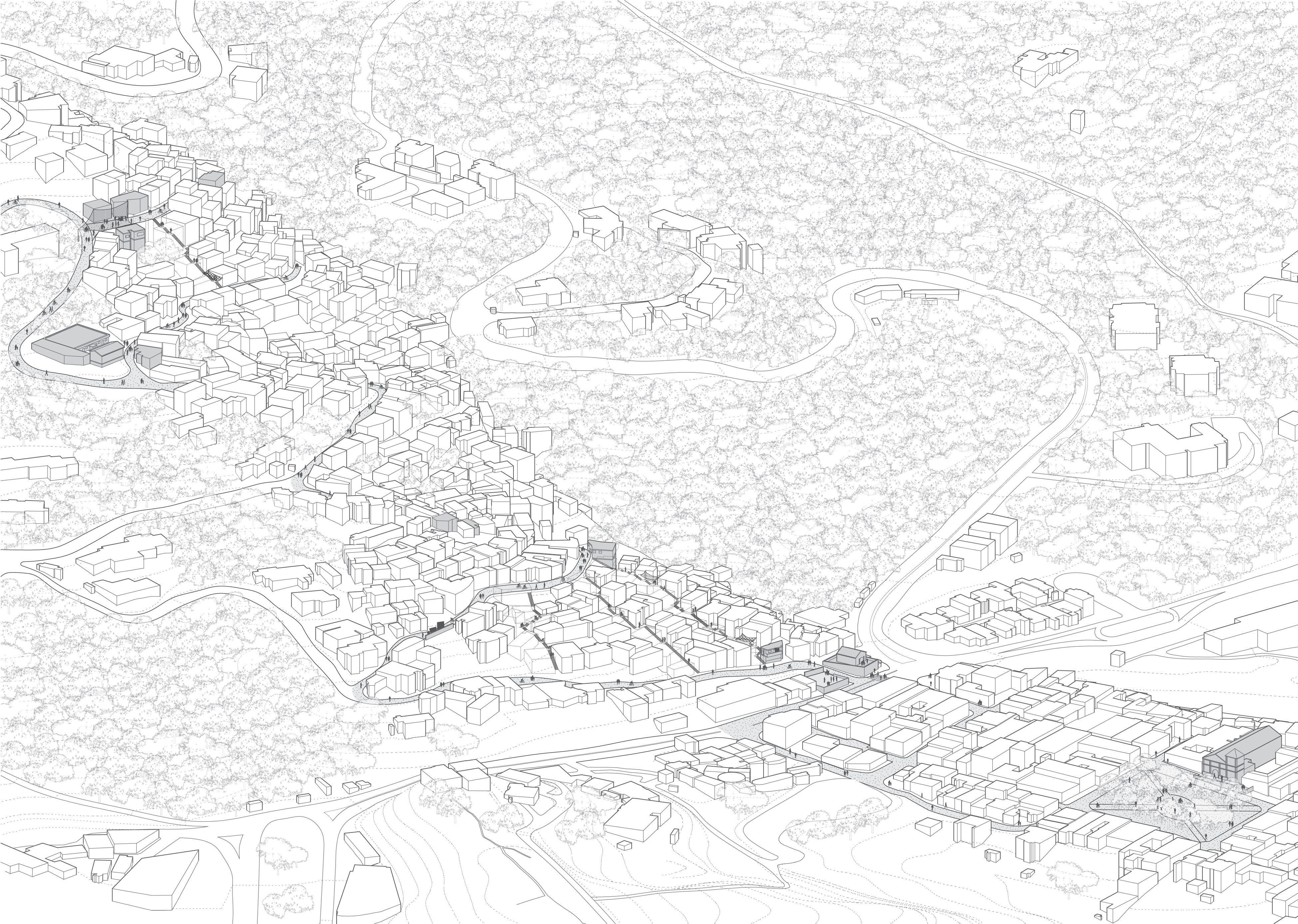

The axonometric drawings that illustrate the publication Pure Space: expanding the public sphere through public space transformations in Latin American spontaneous settlements,1 (Silva, 2020) represent squares and parks in barrios operating as containers of activities and movement. They suggest a desired fluidity that precludes unspoken territorial barriers. The possibility of visualizing this aspiration through drawing begins a process of imagination, familiarization and eventual naturalization of city as hybrid, diverse, indissoluble and complete. Drawing can generate a critical process that recognizes and re-signifies barrios into integral parts of the cities they help form. (fig 1)

Bruno Latour, in his essay “Visualization and Cognition: Drawing Things Together,” explores the role of engravings and inscriptions in the conquest of knowledge and the construction of reality. (Latour, 1986) He argues that the production and dissemination of portable and fixed objects through drawing allows the represented subject to become knowable and real. Drawing can also be used to unite and even fuse reality with fiction. The axonometric drawings of barrios analyzed in this text are both an invitation to acknowledge what already exists and to yearn for a future integrated city that includes all its neighborhoods.

El Calvario in the municipality of El Hatillo in Caracas is a barrio that dates back to the 1930s . It is closely tied to the dynamics of the historical colonial town of El Hatillo, reflected in the lives of families who frequent workplaces, schools and businesses in both sectors. However, people who live in the rest of the municipality or who come to visit El Hatillo, the barrio remains unknown. The aerial axonometric drawing (Figure 01) records an annual event that has taken place every December since 2015, called “El Calvario Puertas Abiertas”, and whose purpose has been to seduce people to get to know the barrio, by attending concerts, book and poetry readings, participating in the ‘Christmas parranda’ and engaging a series of curiosities and artistic interventions.2 Each year the repertory of activities grows. The fluidity of pedestrian movement between the two territories confirms them as one, even though it is simply the manifestation of a quotidian reality for the barrio´s inhabitants. Shades of grey in the drawing show the public space sequence that ascends from the Plaza Bolívar of El Hatillo - right side - crosses the main avenue and winds its way to the top of the barrio reaching the Plaza La Cruz - left side. The territory’s continuity is enjoyed through experience. The reward is felt upon reaching the top of the barrio, where deep views over the town of El Hatillo and the rest of the municipality can be appreciated. Furthermore, the discovery of a new place and the opportunity to expand one´s cognitive limits of the city can produce a sense of satisfaction. (fig 2)

The relationship is similar between the barrio La Palomera and the historic center of Baruta, also in Caracas. Just south of Baruta´s gridded blocks and town square, La Palomera rises over a hill that is perceived as a vertical wall of houses, and conceptually as an impenetrable territory for many surrounding neighborhood. Andy et, like El Calvario, the first inhabitants of La Palomera arrived in the 1930s. The aerial perspective (Figure 2) records the celebration of “La Cruz de Mayo” and the Mobile Museum that took place in May 2019. The event began in Baruta´s Plaza Bolivar with musicians and a 1:200 scale model, measuring 3 x 3.4 meters. Divided into 12 segments, the model represents the barrio La Palomera and the urban fabric beyond. Pieces of the model were carried in a procession from the town square, through the Salom Street entrance and up the barrio’s walkways and stairs. The porters and musicians sang ‘décimas’ interspersed with the rhythms of the cuatro (a Venezuelan string instrument), drums and maracas, as they proceeded along the route. The model was assembled once again at the top of the barrio and became the instigator of conversations about the nature of the city, differences in the urban fabric and how people interpret these differences. The image highlights the space of pedestrian movement in the form of streets, squares, walkways and stairways. It also shows the proximity and spatial continuity between the town and the barrio and encourages the perceived borders between them to be reconsidered and dissolved. (fig 3)

Another example, this time in Carioca land, is the forest reserve above the favelas Chapeu Mangueira and Babilônia in Rio de Janeiro. The favelas skirt part of the morro just north of Copacabana Bay. In the drawing (Figure 3), we see a mountain covered in dense, lush forest, but this was not always the case. In spite of a decree that gave the morro the name Carioca Municipal Park and designated it an environmental protection area in the 1980s, a decade later, the forced displacement of people from other communities resulted in the expansion and densification of the favelas, and the morro was completely deforested. In 2001, the neighbors themselves, with the support of the “Morar Carioca Verde” program, began to repopulate the hill with trees. Today, the park is frequented by people from other parts of the city and visitors who arrive from Copacabana and walk through the favelas to access the natural reserve. In other words, the barrios are understood as figurative passages that connect the local population with the commons. Furthermore, the community is the protector of this public space, understood no longer as its backyard but as a destination at the metropolitan scale. Their role as stewards of the land, mediators and connectors transforms the city´s narrative. The drawing shows how the streets and sidewalks of Copacabana are the beginning of a route that continues along the favelas’ walkways to then become dirt paths through the park. The rocky summit is reached through a clearing, frequented by the favela´s youth flying kites, and by visitors taking in the stunning views of the ocean bays and the other surrounding morros. (fig 4)

A path that begins in one place and arrives at an urban lookout point in another, is often part of a narrative that allows territories to flow into each another. The Cerro Santa Ana and Las Peñas are barrios on a hill that abuts the colonial grid of Guayaquil and the Guayas River. Because of its high elevation and strategic location, this hill once served as a defense post for the city during the 16th. Century. Today, the hill is populated with self-built constructions and their inhabitants belong to a socio-economic level that contrasts with that of their surroundings. After significant public and private investments to rehabilitate the riverfront – known as the Malecón 2000 project - the Municipality of Guayaquil extended its area of influence to include the hill. The gesture was meant to address the security problems, robberies and assaults, allegedly coming from people living in the barrio. The resulting urban investments made in Cerro Santa Ana and Barrio Las Peñas physically transformed their public spaces and the facades of many houses, but also promoted entrepreneurship and helped formalize the tourist businesses that emerged because of their new connection to the Malecón 2000. The drawing (Figure 4) shows Cerro Santa Ana in the foreground and the northern end of the malecón in the distance, linked by a continuous pathway that leads into the barrio. A long series of stairs flanked by houses, restaurants, and bars accesses an expansive oblong esplanade at the zenith, marked by a tower and chapel at each end. From here, an impressive 360-degree view over Guayaquil can be enjoyed. Thus, the barrios Las Peñas and Cerro Santa Ana have become notable tourist landmarks, fully incorporated into the experience and mental map not only of Guayaquileños but also of those who visit the city.

Pure Space’s drawings often construct scenes conflating activities that usually occur at different times into a single instant. The streets, squares and parks are highlighted as places lived with intensity and the aerial view allows them to be understood as a continuous, legible space within the city, where people are the protagonists. The chosen frame portrays a territory sufficiently broad so as to present each barrio definitively inserted in and enveloped by their surroundings, underscoring and making absolutely clear their assimilation as part of the city.3 The drawings’ point of view resonates with bird’s-eye perspectives of cities such as that of Rome by Antonio Tempesta’s in 1593. The drawings’ content recalls the illustration of Nancy as presented in La Place de la Carrier by Jacques Callot in 1637 which records an urban procession. The engravings insist on communicating a curated reading of the city: a 16th century Rome that has recovered the physical extension and perhaps also the ego of its imperial foot print; a procession in Nancy that renders its public square into a stage set and urban life into theatre. In the case of Pure Space the drawings communicate the yearning of a self-built urban territory to be universally recognized alongside the rest of the city, and the city´s request to be acknowledged as diversity. (fig 5 & 6)

Bruno Latour, in his essay “Visualization and Cognition: Drawing Things Together”, explores the role of engravings and inscriptions in the conquest of knowledge and the construction of reality. The production and dissemination of portable and fixed objects through drawing essentially allows what is represented to become knowable and real. “By working on papers alone, on fragile inscriptions which are immensely less than the things from which they are extracted, it is still possible to dominate all things, and all people. What is insignificant for all other cultures becomes the most significant, the only significant aspect of reality.” (Latour, 1986)

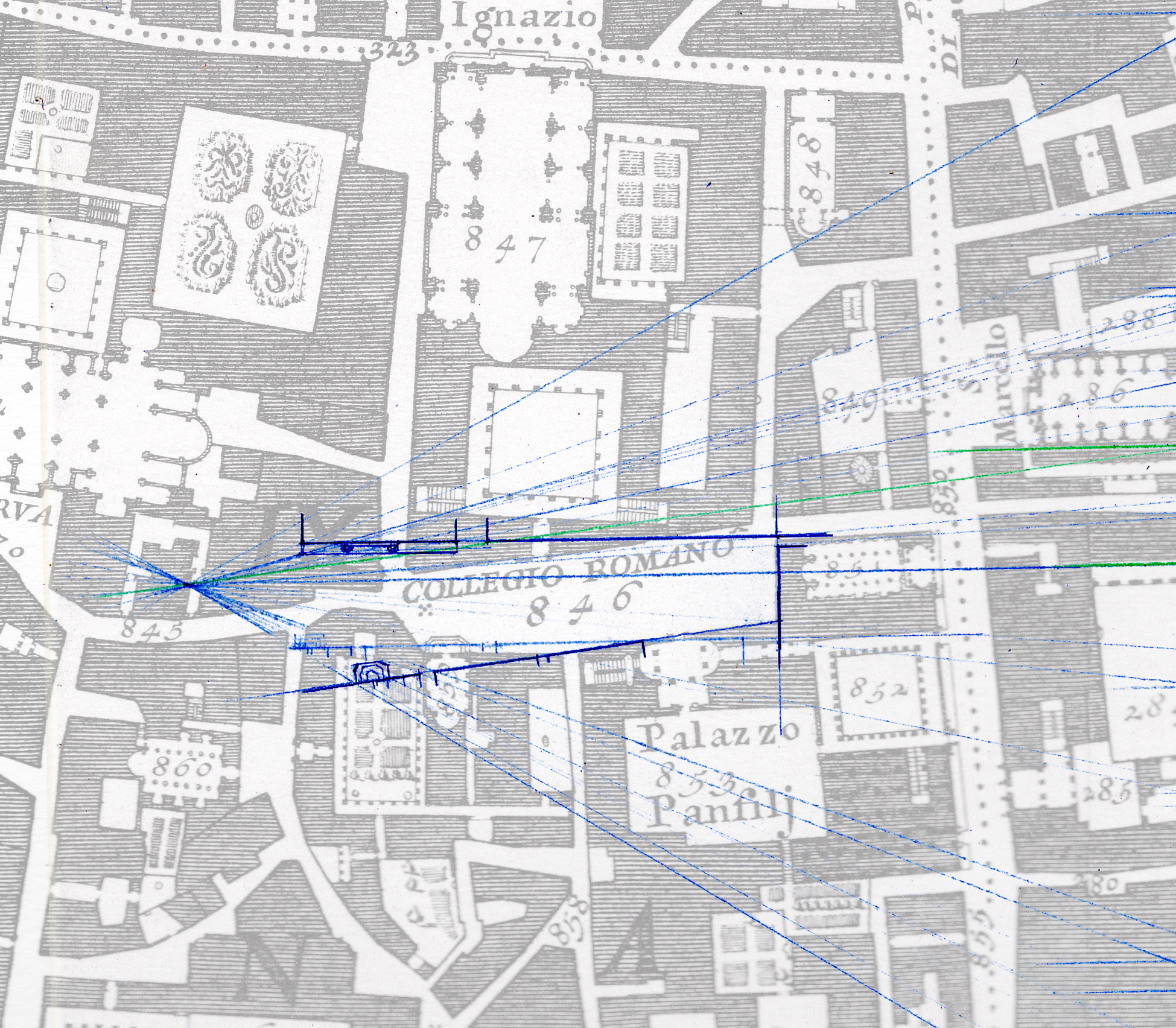

A brief digression based on research I did in Rome between 2005 and 2006 on the 17th century engravings of Giovanni Battista Falta, may help illustrate this concept. Many of Falda´s perspectives feature urban works commissioned by Pope Alexander VII. The Chigi Pope was a passionate urban designer, known for having a large-scale model of Rome in his bed-chamber, which he used to fantasize and project his urban interventions (Krautheimer, 1987). Unfortunately, he did not get the chance to build to the extent he envisioned, since by then the power and wealth of the papal estates was significantly diminished in contrast to the empires of France, the Iberian Peninsula and Great Britain. Alexander VII was forced to check his ambition and commission less- expensive projects that recycled already standing buildings, modified façades, and carved formal squares out of existing outdoor spaces. These interventions are recorded among the more than 80 views of Rome that Falda produced in his short life, compiled in three publications known as the Theatri of modern Rome (Falda 1665, 1665, 1667).

A salient aspect of Falda´s images - and what relates them to the drawings of Pure Space - is that they do not represent their subjects faithfully, but rather significantly exaggerate the dimensions of their squares and buildings so as to appear larger than their actual size. They also separate, angle or eliminate elements to improve the visibility and clarity of the subject. A city fitting the scale of the craved progressiveness, monumentality and power of Rome emerges in the drawings, as though they were eager to compete with their fame and wealth of other cities through imagery. The narrow medieval streets of Rome are turned into fictions of amplitude, assisted by the perspective technique which proves to be a perfect tool to both pay homage to Alexander VII’s urban transformations and “correct” or bring their size closer to that of the creator´s ambition. The difference between the actual dimensions of the Roman streets and squares and those expressed in the drawings can be appreciated in the plan reconstructions of the perspective superimposed on Giambattista Nolli’s plan (fig. 7).

Falda´s depiction of the Chiesa Santa Maria della Pace and the alleyway leading to it - designed by the architect Pietro da Cortona in 1665 - presents yet another distortion strategy. The width of the passage is narrow, and slightly skewed with respect to the church´s axis (Figure 8). Falda’s engraving appears as not one but several perspectives, conflated into a continuous scene, stitching together reality and fiction (Figure 9). Scenes of Rome in the form of engravings such as these were widely circulated by pilgrims each year. They made it possible for myriads of people who had never been to Rome to known and understand it, essentially imagining and projecting a parallel vision of the city thousands of miles extra-muri. By re-dimensioning space Falda’s tricked representations go beyond re-producing Rome: they also re-signify and even re-create the city. (fig 8, 9 & 10)

The correlation between the Roman prints and the views in Pure Space however, does not hinge on technique or quality, but rather on the power of drawing to sublimate the desire and ambition of a place. Both the Santa Maria della Pace and Cerro Santa Ana representations support an urban narrative intentionally conveyed to their audiences. The engraving of Santa Maria della Pace produces the illusion of an instantaneous scene that can only be understood that way by traversing it in time. The continuity and breadth of the space and the design of its façade are not only precisely the features commissioned by the Chigi Pope but also communicate that there is enough room to accommodate a carriage, which in the 17th century was considered crucial to a building’s status. By carving away space in front of the church, Da Cortona confers the status and relevance Alexander VII sought for the tomb of his uncle, banker Agostino Chigi, whose chapel there remains decorated with 15th century frescoes by Raffaello di Sanzio. In the case of the Cerro Santa Ana drawing, the illusion of continuity is achieved by using an elevated viewpoint - a bird’s-eye view - which visually merges the boardwalk along the river with the ascent to the top of the hill. The single path sustains that this is an integrated and connected urban fabric, in clear opposition to the fragmentation that once existed and probably still endures in the mental maps of many. The political and social agency of the drawing lies in how it facilitates the introduction, recognition and eventual naturalization of a once contentious space both for the people that live there, and for those who encounter it through the image.

It is also important to consider the authoritarian and manipulative weight of the drawing. Latour warns that mapping and drawing territories belonging to others is, in a certain sense, colonizing the ethnographic subject, since mapping in itself is an act that only an outsider feels the need to perform: “we map their land, but they have no maps either of their land or of ours” (Latour, 1986). Undoubtedly, in our practice, we have consciously used drawing to legitimize barrios. Six years ago, we mapped the growth of all the Caracas barrios over a period of 48 years. CABA: Cartografía de los Barrios de Caracas 1966-2014, which made a part of the city visible through historic and planimetric records. It also motivated a readjustment process regarding the nature of the city, since the publication revealed that half of Caracas’ residents live in barrios (Silva, 2015). In more recent years, and in line with Latour´s remark, we have worked on facilitating broad participation through events, conversations and shared design processes – to take advantage of and incorporate as wide a knowledge base as possible, pluralizing interpretations of space and the city and shifting the architect’s role away from controlling content.4

Latour ends his essay by redeeming drawing without reservation. He celebrates its effectiveness in uniting and even merging reality with fiction, not only as an instrument of power, but also as a strategy that allows us to constantly re-arrange and rewrite narratives. It is a skill that frees us from outdated, moralistic or exclusionary concepts and helps us replace them with new interpretations and discourses. The aerial views of the barrios presented in this essay are both an interpretation of the real and an invitation to long for an integrated and complete city. Acknowledging the barrios is fundamental to safeguarding the well-being and productivity of the people who live there. But it is also critical to conservating and promoting the diversity and cultural richness produced through the collective efforts of communities over time. Without the barrios, the city is poorer. Without barrios, a heritage that has been cultivated and labored for generations is lost. The construction of new urban narratives and the visualization of possibilities for real integration - exemplified in the image of an anticipated city - is fundamental to induc consensual changes in public policies, improving the quality of services and education, and developing greater economic productivity. In this way, advances towards the realization of a complete city are attained not only in rhetoric but also in practice.

Notes

- This research was conducted as part of the Harvard University Wheelwright Fellowship awarded in 2011. The publication was funded by the Graham Foundation for Advanced Studies in Fine Arts and CAF development bank of Latin America.

- El Calvario Puertas Abiertas is organized by the community and Ciudad Laboratorio.

- The drawings were produced from virtual three-dimensional models. These were produced on the vector planimetry of the cities. The neighborhood and favela floor plans were created from satellite images in Google Earth, as they are not usually accessible to the same extent as the "formal" areas. Once the views of each model have been chosen, they are exported as a two-dimensional drawing and complemented with detailed information, plots and people recording the various activities in the public space.

- Projects organized and led by Enlace Fundación and Ciudad Laboratorio: "Integración en Proceso Caracas" 2018-2020, project Rio Guaire 2020-2022, the transformation of the Annex and Casa de Todos in La Palomera into a center for art and culture.

References

- Falda, G.B. (1665). Il Nuovo Teatro Delle Fabriche, Et Edificii, In Prosepttiva Di Roma Moderna: sotto il Felice Pontificato di N.S. Papa Alessandro VII.

- Falda, G.B. (1665). Il secondo libro del nuovo teatro delle fabriche, et edificii, fatte fare in Roma, e fuori di Roma dalla santità di nostro signore papa Alessandro VII.

- Falda, G.B. (1667). Il terzo libro del novo teatro delle chiese di Roma date in luce sotto il felice pontificato di nostro signore papa Clemente IX.

- Krautheimer, R. (1987). Roma di Alessandro VII 1655-1667. Edizionei dell'Elefante.

- Latour, B. (1986). “Visualisation and Cognition: Drawing Things Together” in Elizabeth Long and Hanrika Kuklick (Eds.), Knowledge and Society. Studies in the Sociology of Culture Past and Present; a research annual (pp. 1-40). JAI Press.

- Silva, E. (2020). Puro Espacio: transformaciones del espacio público en asentamientos espontáneos de América Latina. Actar.

- Silva, E. et al., (2015). CABA: Cartografía de los barrios de Caracas 1966-2014. Fundación Espacio.